Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

![The Brontes of Haworth - The Complete Series [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51JxwnH79iL.jpg)

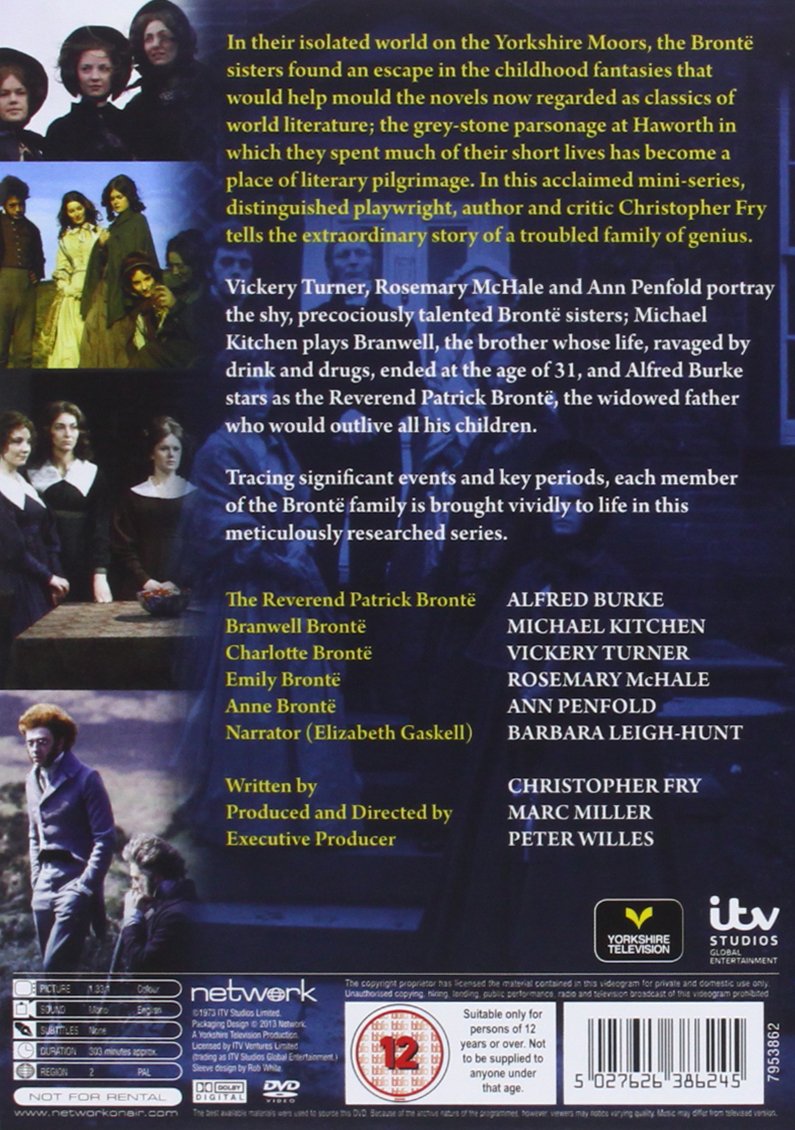

The Brontes of Haworth - The Complete Series [DVD]

J**T

Rescued by writing

This Yorkshire Television production, made in 1973, is very good on subdued atmosphere: cold eastern winds; rain, sleet and snow; rutted roads; muddy horse carts; broken cobblestones; dark candlelit rooms; coal fires; stone floors; the slate-grey churchyard, cemetery and parsonage; and of course the bleak, seemingly lifeless West Yorkshire moors. The effect is one of isolation: the family, vicarage, village — not much beyond. Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte’s famous biographer, said the road from nearby Keighley to Haworth was the longest four miles she had ever traversed:“It was toward the end of that summer [of 1849] that I first visited the parsonage. Charlotte had written to me, ‘Come to Haworth as soon as you can. The heath is in bloom now. I have waited and waited for its purple signal as a forerunner of your coming.’ I left Keighley in a cart for Haworth four miles off — four tough, steep, scrambling miles.”Haworth was bleak in winter for sure, and it’s hardly on the road to anywhere important. But it’s not on the dark side of the moon, a place cut off from the outside world.For one thing, the world came to the Brontë family in the form of books and literary magazines. All the Brontë children were studious and literary, writing from a young age under the patronage of their parson father Patrick, a published poet himself who had studied at Cambridge and taught them to be diligent and bookish. Unsurprisingly, he was also a voracious reader and collector of books. Also, being Irish, he had little choice, perhaps, in being a great storyteller. The children grew up with his tales and eventually created worlds of their own in prose, inspired by a collection of toy soldiers their father brought home for Branwell on his son’s ninth birthday in 1826. The eventual result was Glass Town, Gondol and Angria, imaginary realms as real to the children as daily reality, the history and characters of these kingdoms chronicled by them in tiny script in small composition books. Without these worlds “Jane Eyre”, “Wuthering Heights”, “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” and Emily’s extraordinary poetry would likely never have been written.Secondly, the girls did travel. They knew Halifax, Bradford, Leeds, Manchester, York and Scarborough on the east coast. Charlotte and Emily also knew the Continent, having lived in Brussels where they studied French and German for a year, their aim to start a school for girls in Haworth. However, the plan did not succeed, or not well enough to satisfy them. Thus writing, always a private passion, became an economic necessity for them when they finally conceded that Branwell would amount to nothing professionally. The hopes of the family had been high with him, the only son and brother, thus forming a pressure he wasn’t able to cope with. He had wanted to be a painter. In fact, the famous portrait of his three literary sisters — which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London — is his. He had hoped to attend the Royal Academy in the capital, but when the time for exhibiting came his nerve failed him. Instead, he didn’t get beyond the taverns of Halifax on the way to London, drinking away the travel money his father had given him. Forced then by fate, the sisters turned to writing as a source of income.In voiceover, the actress Barbara Leigh-Hunt as Mrs. Gaskell introduces the drama through her narration:“In the West Riding of Yorkshire there is a moorland village. A street climbs up so steeply that horses at the time I am speaking of were in constant danger of slipping backwards. The name of the village is Haworth. At the top of the hill where the horse breathes more easily a lane leads to the church and sexton’s house and Haworth parsonage. The wind blowing off the moors would never have been heard by us if it hadn’t been for the parson’s four children, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne.”The sisters stand stock still in the parlour of the parsonage, posing for Branwell as he adds touches to his portrait of them. Emily, the stoic, is the tallest and most beautiful. Anne, pretty and delicate, pouts. Charlotte is plain and small, even mousey. The painting is off-kilter and strange, so asymmetrical, Anne and Emily to the left, Charlotte to the right, a large gap in the middle. Why? Because the painter has painted himself out of the picture, its centre empty, ghostly. It’s as if he knew he didn’t belong in it. Not with such clever sisters, so dedicated, self-believing and ambitious as they were. Maybe he was always on the verge of cracking under the strain. Nobody drinks to a state of stupefaction to find happiness. What they seek is oblivion, and this Branwell regularly found, a prelude to his destruction.The series is not literary per se. The books and poetry are in it of course, on the shelves and talked about, but hardly featured, so the series can’t tell us why “Jane Eyre” and “Wuthering Heights” are classics of English literature. Instead, it focuses on a particular family, village and time.What’s interesting in a strange and paradoxical way is how banal and ordinary the lives of the sisters were. The parsonage, village and moors largely made up their world. In the parsonage they baked, cooked, sewed, darned, swept up. They also read and wrote of course, but this was part of their domestic routine, their regular daily life — writing for themselves and their own amusement, as opposed to publication for the world. That would come later when necessity demanded it. In the village they shopped, sent letters at the post office, gossiped with neighbours. On the moors they gathered wildflowers and heather, walked the dogs, sought and found seclusion from the village. The parsonage had a piano. But if the girls sang and danced, they didn’t do it publicly at social balls, as by and large there were no social balls, or none they were invited to. No romance, courtship, stolen kisses in the moonlight. Branwell was the family Romeo, though not a very good one, as his lover was not a young Juliet. She was a Mrs. Lydia Robinson, the middle-aged wife of the employer of his sister Anne who worked as a governess at Thorpe Green, the estate of the Robinson family in the nearby town of Mirfield. The Reverend Edmund Robinson was both sickly and neglectful of Lydia’s needs. Branwell was not, which delighted Lydia. He was young, guileless, virile, the perfect toy-boy object she evidently desired. And so they loved at cross purposes, she for pleasure, amusement and diversion, he for passion and position, meaning greater social standing. Both indulged in guilty thoughts regarding Rev. Robinson’s eventual demise, though each entertained different versions of a future it would bring. Branwell saw himself married to Lydia, despite being nearly 15 years her junior. She saw herself free and financially independent. When the reverend’s death finally came she grieved behind her black widow’s veil, but the veil hid more than grief from others, including Branwell. He wasn’t the only man she had had her eyes and hands on. Branwell had his charm, wit and vitality, but his pennilessness, debts and fondness for drink weren’t part of the charm Lydia enjoyed.Some take heartbreak, disappointment, emotional set-backs in their stride, looking ahead and farther afield for other hopeful opportunities, patiently believing their time of steadfast love will come. Branwell was not one of these. He was narrow in ambition, and even in romantic imagination. Why was it that Lydia had to be the only one for him? Some say mother complex. Branwell barely knew his own mother, she having died in 1821 when he was only four. This might explain his obsession and fixation with Lydia.At any rate, failed love for him became further proof of failure in other realms of life. He didn’t get over this lost love, choosing drink, drugs and self-pity as substitutes for it. His gradual decline takes up a large part of the story, as it helps make the ambition of his sisters credible and comprehensible. Branwell as deadweight forced them to write with an eye toward publication, his debauchery an ironic spur to their ambition.Anne was the first to openly admit the desperate need to publish. What else could they do? Anne hated being a governess and Charlotte felt the same about teaching. Emily had no professional interests beyond writing. So it was fixed: they must write and be writers. A covenant or pact formed, especially after Anne announced she was writing a novel (“Agnes Grey”, based on her experiences as a governess). When Charlotte and Emily returned from Belgium the three sisters agreed to jointly publish a book of their poetry (with £50 of their own money advanced toward publication). What finally pushed this plan into action was Charlotte’s discovery of the brilliance of Emily’s poetry, far and away the best in the collection — original, passionate, insightful. If Wordsworth knew the Lake District hills and dales, describing them immaculately, Emily did the likewise with the West Riding moors of Yorkshire. She owned them emotionally. No one has ever described them as brilliantly and passionately as she has, and that includes Ted Hughes who is no poetic lightweight.The poems were published in 1846 under the title “Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell”. The collection sold two copies, not exactly an auspicious beginning to their writing careers. However, a few intelligent critics took notice. The poems of Ellis in particular (those of Emily) astonished these critics. This praise ennobled and empowered the sisters, because even more important than money to them — or just as important — was respect. They knew they could write and had important things to say. Things about women, their needs and desires and place in society; things about love, including sexual love; things about nature and beauty; things about religion and spirituality. Though they were country girls, they were radical, early feminists without trying to be or thinking they were. They were simply honest. And brave. And persevering. They believed in themselves and what they had to say, and all these things created a minor revolution in the romantic tradition of novel-writing at the time. Jane Austen, among others, had previously created beautiful female protagonists. But her women are always situated in the comfort of gentry country society. They are too well cared for to rebel. Not so Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey. They will have what they feel is rightfully theirs. Or Catherine Earnshaw. Who was this creature of animal appetites, of passionate loves as extreme as the wild and tempestuous moors? These characters were unique because the Brontë girls were unique. They may have imitated Lord Byron, Sir Walter Scott, Shelley and Wordsworth, but the voice that comes through is their own. They were literary creatures made by books, religious seclusion, geographical isolation and wild nature. They were a one-off, a conclusion the world would eventually come to make.Branwell died on 24 September 1848, aged 31, the ravages of alcohol abuse having weakened him. He suffered fevers and delirium tremors. Bad colds turned into pneumonia, which worsened into tuberculosis, brought on by malnourishment and a weak immune system. His TB, called consumption in the day, was the galloping sort, which meant it was fast and short in duration. It was also highly contagious. He should never have been allowed to die in the parsonage. But since it wasn’t quarantined, others were exposed, including Emily and Anne. Emily died of tuberculosis on 29 December 1848, just three months after Branwell’s death. Anne lasted a little longer, but only till May 1849. Charlotte and her good friend Ellen Nussey took Anne to Scarborough to die. She wanted to be near the water, waves, sand, open sky, she said. In the film she rides in a horse cart along the beach. There is no driver but her. She holds the reins and makes the horse walk on. Up the beach she sees a tall figure in black, a thin young man wearing a top hat. In the distance Anne sees William Weightman, a curate at Haworth Church who assisted her father Patrick. William died of cholera seven years ago. In church during the services he often looked at Anne out of the corner of his eye. It was an open secret that he loved and desired her. But Anne did not reciprocate these feelings, even knowing his were sincere and genuine. We can’t be sure why, but we are sure now, at least in this film, that she hasn’t forgotten him. Now, close to death herself, she sees him coming up the beach toward her. But this William is a phantom, a fragment of memory and desire. The man who passes the horse cart is a stranger who does not speak or even nod to Anne. William is lost to her forever, just as life soon will be for her too.Emily was the same as Anne: no man, love, sex. As far as we know, at least, all their passion spent in their books.Charlotte’s fate would be different. She survived the terrible onslaught of 1848-49. Her constitution must have been stronger, as was Patrick Brontë’s. He outlived them all — his wife and six children. Now, in the summer of 1849 when Elizabeth Gaskell first visits Haworth, Charlotte is all that remains of Patrick’s large family.Arthur Bell Nicholls had also been a curate in Haworth, as William Weightman had. He worked with Patrick Brontë for a dozen years. He knew the family well and was lovesick for Charlotte for many years. But he was timid and decorous and could not declare himself. Also, he feared Patrick, the grand patriarch of both the church and parsonage. He didn’t dare broach the subject, rightly fearing how Patrick would react. With Charlotte too it was difficult. By 1849 she was no longer Currer Bell. The rumours that first spread in London were proved correct: C. Bell was actually Charlotte Brontë. In time, by 1850, the whole world would know, including the little world of Haworth. This presented Arthur with even more difficulties. He loved Charlotte the person, the woman, the individual, not Charlotte the famous author. He could take her as a famous author, but even Charlotte knew he loved her for who she was, not what she was.Time passes and finally, ravaged by guilt and desire, Arthur unburdens himself to Charlotte, confessing in 1852 that he’s going mad without her, unable to conceive of life without her. How to live? What to do? He can’t say. He’s at her mercy now.She likes and respects him, but has never thought of love in relation to him. Charlotte marry a clergyman after every unflattering thing she has written about clergymen in her fiction? It seems ludicrous. But as time passes she realizes she’s just like Arthur in a most important regard: she likes the man, who he is. What he does becomes immaterial.But drama will occur, as no Brontë love is ever easy. Patrick banishes Arthur for the temerity the curate had in thinking he could be the equal of Patrick’s famous daughter. It isn’t worth discussing. So Arthur is exiled. But not from Charlotte’s mind. He takes another job as curate in some northern district. He had an offer to go south but turned it down, wishing to stay close to Charlotte. Months pass; their letters accumulate in drawers. The depth of Arthur’s feeling remains unchanged, which is to say steady. By degrees Charlotte softens, and little by little she warms to the feeling that she’s being so actively courted, especially at her age now (35).Patrick may have been the patriarch, but Charlotte, just like Jane Eyre, has a will and mind of her own. The time for her happiness in matrimony has come. It is hers, not his (her father’s), and she is prepared to seize it.They were married on 29 June 1854 in Haworth Church, the very place where Arthur had preached for so many years and where Charlotte had sat, prayed and sung hymns all her life. They were happy, devoted to one another. They honeymooned in Ireland where Charlotte met many of her new Irish in-laws (as Arthur, just like Patrick, had come to England years ago from Ireland for his religious education).Charlotte fell from a horse while riding in Ireland and also caught a chill and bad cough. She recovered when they returned to Haworth during that summer of 1854, but that autumn while walking on the cold, rainy moors she had a relapse. Also, she had discovered she was four months pregnant. The first in the next generation of Brontë’s was on its way. But Patrick Brontë’s luck with loved ones was never good. Tragically, he would never become a grandfather, even though he clearly looks like one in the series with his grey hair and proud bearing.Charlotte died on 31 March 1855 from a combination of causes, not helped by the difficulties of a first pregnancy at her age (38). She is buried in the Haworth church cemetery with her brother and three of her four sisters, including Emily. Only Anne is buried far from Haworth — on the coast at Scarborough, which is what she wanted.Arthur and Patrick shared their grief together for the next six years, Arthur residing in the parsonage with his father-in-law until Patrick’s death in 1861, aged 84. Arthur had wanted to stay on as vicar of the church but the trustees voted against him. Thereafter he returned to Ireland and re-married in 1864, leaving the church and becoming a farmer. Charlotte willed the copyrights of all her works to Arthur, knowing they would be in safe hands. She was right about that, as he fiercely protected her reputation to the end of his life, dying in 1906, aged 87.Elizabeth Gaskell’s hagiographic biography of Charlotte was published in 1857 (“The Life of Charlotte Brontë). Charlotte and her sisters had already been famous prior to the publication of this book, but what is now called the Brontë cult started in 1857 (and shows no sign of retreat 160 years later in 2017).A beautiful new film about the Brontës called “To Walk Invisible” was released last year and is now out on DVD. It’s a feature film of two hours and much nicer to look at with its superior production values than “The Brontës of Haworth”. But this older film here benefits in many ways compared to the newer production. First, the pace is leisurely, just as life at the parsonage was. It spans more than five hours and is historically accurate in the copious detail it provides. Second, its mood seems perfect to me: bleak and slightly repressive. The parsonage was strict, the rules rigid in many ways. Patrick loved his children but ruled with a very disciplined hand. Third, the writing (by renowned playwright Christopher Fry) is superlative. A literary family needed a very literate script and got one here. Fourth, the clothing, shots of Haworth, interiors of buildings (the parsonage, church, pubs and inns) are excellent. And fifth, the music, melancholy and slightly nostalgic, is moving, its score dominated by oboes, clarinets and flutes, wind instruments that perfectly match the winds blowing across the harsh and rugged moors.They were extraordinary, the Brontë sisters, even when seen in their ordinary, everyday worlds in Haworth and elsewhere. Their minds were rich and imaginative, teeming with characters, incidents, stories. Fate conspired to make them the daughters of a highly educated and well-read Anglican clergyman growing up in a remote, isolated and wild place. They had their father, books, toy soldiers and each other for stories. They had paper and pencils, imagination and encouragement. If Branwell had stuck to his painting we would have even more portraits of the famous sisters. However, George Richardson’s famous portrait of Charlotte (1850, chalk on paper), captures her essence perfectly. In it she looks dutiful and intelligent, the eyes attentive, the forehead high, the look loving and sympathetic. She wrote in anger and frustration sometimes because she wanted a better world for everyone to live in. But mainly she wrote in the spirit of love — love for nature, goodness, charity, equality. She loved her family and friends, and it’s clear she loved life too even with all its disappointments, heartache and grief. In the end she made Jane find love and happiness with Rochester, and in her life too she found both with a good man named Arthur Bell Nicholls.She called herself Currer Bell as an author, not Currer Brontë, long before she married the man with the middle name Bell. What does this say? Maybe that she had her eye on him all along but was too shy or clumsy or inexperienced to know how to proceed. She lived in a parsonage under the stern gaze of her dominant patriarchal father. She hardly knew what being a woman was except in her vivid imagination. But her passion was always there, just as it was in Emily and Anne, and all you need do to feel it is read the books in the spirit in which they were written.~ • ~ • ~ • ~Production and year: Granada, Yorkshire Television, 1973, distributed by ITVScreenwriter — Christopher Fry (1907-2005)Director: Marc MillerPatrick Brontë — Alfred Burke (1918-2011)Charlotte — Vickery Turner (1940-2006)Emily — Rosemary McHaleAnne — Ann PenfoldBranwell — Michael KitchenArthur Bell Nicholls — Benjamin Whitrow (1937-2017)Elizabeth Gaskell — Barbara Leigh-Hunt

O**O

Interesting and with a rather authentic feeling

I bought this with trepidation because most of the reviews are so negative. Having seen the serial, I am now really surprised at the extent of the negativity.This serial is not up among the greats - 'I Claudius', 'Pallisers', 'Jewell in the Crown' 'Brideshead' etc. But it is very good.As far as I can tell there is considerable accuracy in what is presented about the lives of the Brontes. However, the screen writer does not just slavishly chronicle details of the Brontes' lives. He cleverly contrasts Branwell's failure with the success of his sisters. Central to the success of this is Micheal Kitchen, who wonderfully conveys Branwell's charm and fragility and also his inability to grow up. When he goes to London to seek his fortune you feel his fear and you know he has to go home. Emily is suitably Sturm and Drang. Charlotte shows all the pent up passion of her heroine Jane Eyre and comes across as a bit prudish, with an acerbic wit and quite a bit of get up and go. Finally, Anne surprised me. She was full of gentle courage and forbearance. I came away from the serial loving her and wanting to know more and also wanting to read her books.In terms of the production. It was a bit slow to get going, but once it did, I found myself staying up later than intended for just another episode. The children morphed beautifully into the adults. The adults bear a good resemblance to the portrait of them by Branwell. The final episode though did suffer from a couple of lengthy, rather wheezy death scenes that got a bit irritating. It is for this reason that I rated the production 4 not 5 stars. Otherwise the acting was uniformly good to the extent that I often felt I was watching the real people not actors. I think though it is important to be clear, this production definitely has a stagey feel to it. It is not in any sense glossy. Even though it has been filmed in Haworth and on the moors, it could just as easily have been done in a theatre. The scenery is largely irrelevant, compared to the relationships among the five main characters.There have been complaints about the quality of the film and sound. It is true that the film is showing its age. It is also true that the rustling of the clothes can be a bit annoying and the volume of the music can be a bit high compared to the speech. I think though it is important to judge something within the limits of what technology permitted then and for me these are small complaints. What is important is whether a production has been well written, whether the actors do the script justice and whether the viewer comes away feeling like they got something out of the time that they spent watching. I most definitely did and I am happy to have had the opportunity to see this production rather than not see it because was too expensive to fix problems such as volume, or film.

A**Y

A few rewardingly subtle and dryly comic points; apparently authentic; definitely worth watching

I agree with some of the comments by others here about it taking a while to 'get going'; the initial voice-over grating a little at first etc. But still I have to say I loved this (hence five stars), to the point that I too, like some others here, ended up 'binge-watching', enthralled by the story (even though I know the 'story' already). It DOES appear very accurate with regard to aspects of the Bronte's lives, even to the point of Keeper's brass collar. There are some subtle very dryly comic points in the story too. Two of them are around Branwell and point to brilliant pieces of acting by all in the scenes. In general, I think the drama conveys the ironic difference between Branwell and his sisters' attitudes, explaining Branwell's 'tragedy' (in terms of failure) well. Another possibly unintentional comic point is around Emily's death and Keeper. I'm not sure yet as to how accurate a portrayal of what happened this actually is, but let's just say the dog playing Keeper 'stole the show', and god knows how any of the actors kept faces straight enough to film the scene (especially Rosemary McHale who was playing Emily). I'd love to find out from the actor herself to be honest! Yet the scene was still tragic in itself, and I believe reflects the way Emily appears to have died (indeed she would have been quite wheezy!). TV/Film dramas are different now, and this does have a slower pace than what many of us may be used to. Nevertheless, I thoroughly enjoyed it; it has stayed in my mind for days; and I'm glad I finally got to see it, having missed the opportunity to see it when it was shown on TV in the seventies.

J**R

Second disc damaged.

Disappointed that the second disc is damaged and not really useable. Admittedly this is an old recording, but it should not have been described as being in good condition.

Trustpilot

1 week ago

3 weeks ago