Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

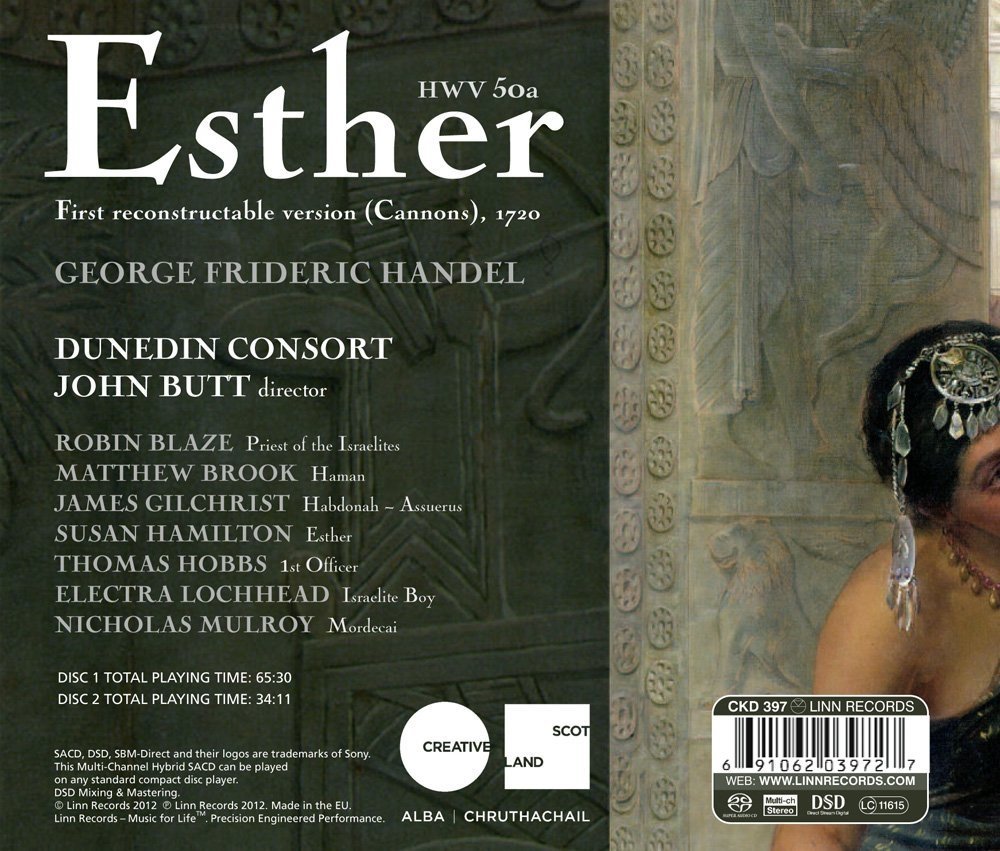

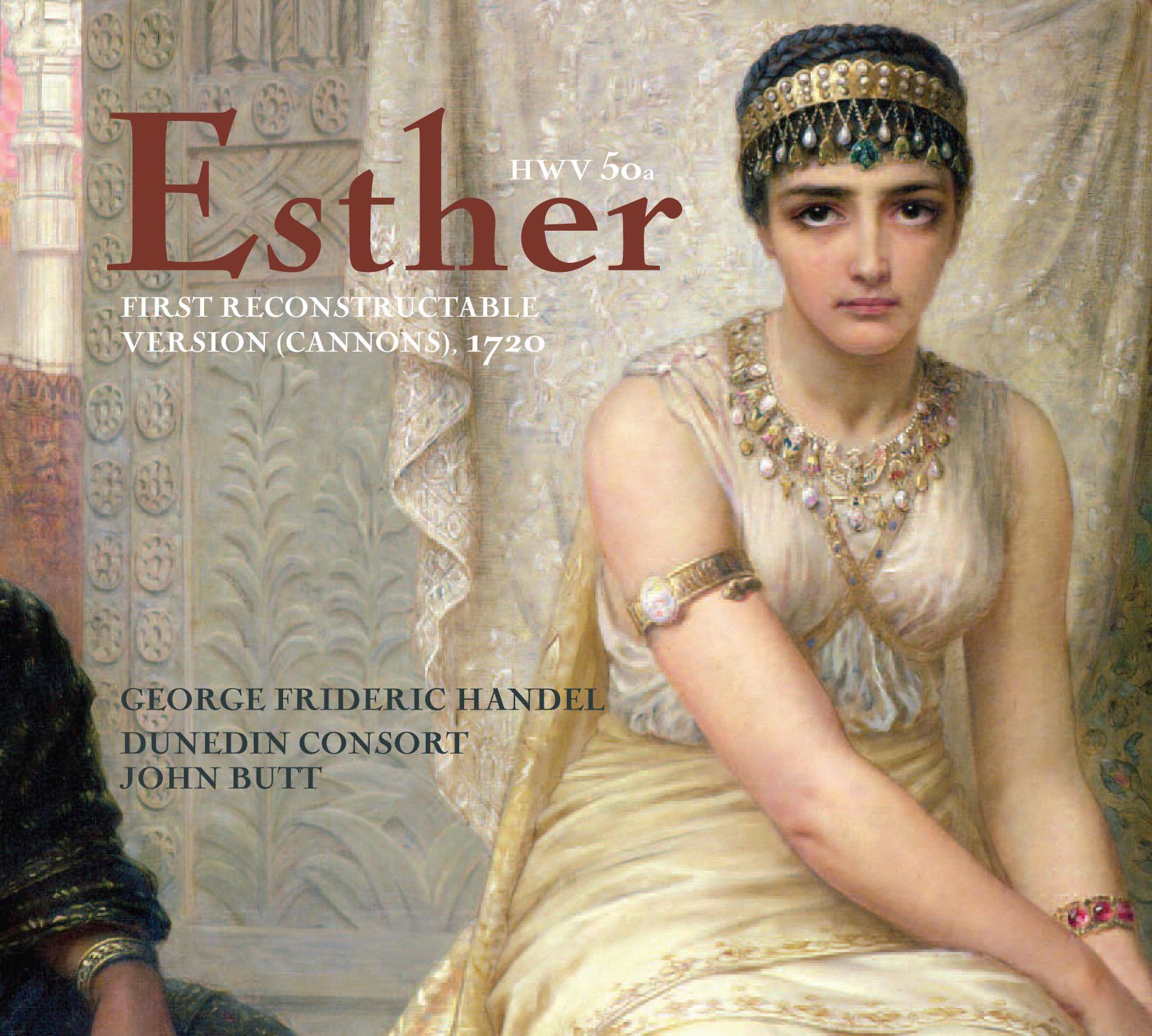

Product description Classica vocale Sacra Oratori - HAENDEL Georg Friederich: Esther (vers.ricostruita 1720) Review Esther is well known to have been the first of Handel's English oratorios, but exactly when it was first heard, and in what form, remains uncertain. The first version, which probably dates from 1718 and may have been performed as a masque, is effectively lost, and Handel made a total revision and expansion of the score in 1732. But John Butt and his Dunedin Consort perform what they call the first reconstructable version of Esther, dated 1720, which is a sacred drama whose significance to Handel's later, better-known oratorios is clear. Butt explains the historical background to the score he has created in his detailed sleeve notes, but as with all his Dunedin performances, and their previous Handel and Bach recordings, the scholarship is only a means to an end, and is never allowed to get in the way of the wonderfully crafted music making. Textures are lean 11 singers, including the soloists, 20 instrumentalists but wonderfully precise, and the solo contributions, with soprano Susan Hamilton as Esther, are models of stylishness. --Andrew Clements - The GuardianFed up with the depressing weather? Access hot sunshine with this bouncy account by the Edinburgh-based Dunedin Consort of Handel's Esther, generally presumed to be the first English oratorio. The CD advises purchasers that the version performed is the first reconstructable version (Cannons), 1720. Indeed it is, though I'd better not go into the scholarly detail lest we both fall asleep. What matters most is not the niceties of the edition used (derived from Handel's original conception of a compact staged entertainment), but the performers freshness and dash. After their past accounts of Handel and Bach we've come to expect youthful verve from John Butt's ensemble. But the singers virile word-painting still grabs the lapels in this striking work, inspired by the legend of the Jewish queen who saves her Persian community from annihilation (as enshrined in the biblical Book of Esther). At the revived version's premiere in 1732, foreign singers so mangled the words the the Persian king's line I comb my Queen to chase the lice . Nothing like that happens with James Gilchrist's king (so powerfully smitten with the Jewess's charms), Susan Hamilton's Esther (so ringingly pure), robin Blaze's heartfelt priest or Matthew Brook's villainous Haman, consonants dipped in venom as he determines to remove all Israelites from the land. Inevitably we think of the Holocaust; the libretto's not always easy listening. Much of Handel's music was appropriated from his Brockes Passion though it fits its new surroundings very well. Along the way, Butt's lean ensemble (19 players) shower us with instrumental delights, building in colour and diversity with delicious harp traceries, the comfortable ballast of two bassoons, and finally a triumphant trumpet when everything turns out happily for everyone, Haman excepted. Handel's musical resources generally open out as the piece proceeds, with the chorus's role increasing in importance. Once again, Butt's forces are small: eleven voices all told, eight doubling as soloists, each singing as if every word matters. That's more than enough to keep us on the edge of our seats. --Geoff Brown - The TimesFed up with the depressing weather? Access hot sunshine with this bouncy account by the Edinburgh-based Dunedin Consort of Handel's Esther, generally presumed to be the first English oratorio. The CD advises purchasers that the version performed is the first reconstructable version (Cannons), 1720. Indeed it is, though I'd better not go into the scholarly detail lest we both fall asleep. What matters most is not the niceties of the edition used (derived from Handel's original conception of a compact staged entertainment), but the performers freshness and dash. After their past accounts of Handel and Bach we've come to expect youthful --Geoff Brown - The TimesButt's direction combines spontaneous freshness with a care for expressive phrasing and precise colouring. The 11-strong chorus - the solo cast plus reinforcement - is vital incisive, packing a fair punch even in the ceremonial final chorus. June 2012. --Gramophone MagazineThe scholarship is only a means to an end,and is never allowed to get in the way of the wonderfully crafted music making.Textures are lean 11 singers, including the soloists,20 instrumentalists but wonderfully precise,and the solo contributions,with soprano Susan Hamilton as Esther,are models of stylishness.The Guardian,17th May 2012. --The Guardian P.when('A').execute(function(A) { A.on('a:expander:toggle_description:toggle:collapse', function(data) { window.scroll(0, data.expander.$expander[0].offsetTop-100); }); }); About the Artist The Dunedin Consort has established a reputation as the finest single-part period performance choir currently performing. In 2011 Gramophone named the Dunedin Consort the 11th Greatest Choir in recognition of its triple focus upon artistic revitalisation of over-familiar great works, meticulous musicological enquiry and the audiophile integrity of Linn Records' production values. The multi-award-winning Dunedin Consort has won praise for the natural style of its soloists (an authoritative bass and a superb contralto-The Guardian) and renown for the virtuosity of its singers. The Dunedin Consort has performed at music festivals in Scotland - including the Edinburgh International Festival and broadcasts frequently on BBC Radio 3 and BBC Scotland. See more Review: Beautiful performance of Handel’s first oratorio - This is Handel’s original, 1720 version of ‘Esther’ as composed for the Duke of Chandos – or rather, as John Butt explains in his scholarly but very readable booklet notes, the first ‘reconstructable’ version following an earlier draft originating from 1718. The composer later revised and greatly expanded the work, resulting in a final version of 1732 (as recorded by Laurence Cummings, listed and reviewed elsewhere). This ‘Esther’ then, Handel’s first oratorio and so the start of a long and distinguished tradition, is given a beautiful performance by the Dunedin Consort directed by John Butt. The graceful period-instrument textures and stylish playing of John Butt’s Dunedin Consort are immediately evident in the Overture, and of course continue throughout - including some lovely solo instrumental work. We get an equally fine team of vocal soloists, including tenor James Gilchrist outstanding in the role of Ahasuerus, soprano Susan Hamilton excellent in the title role, tenor Nicholas Mulvey’s Mordecai, and bass Matthew Brook’s forceful Haman. I don’t think much of countertenor Robin Blaze’s Priest of the Israelites, however - underpowered voice, expression nothing special either - but fortunately he doesn’t have a lot to do here. Special highlights for me include tenor Thomas Hobbs’ aria ‘Tune your harps’ (CD1/9) and its subsequent chorus (1/10); the lovely passages for flute and harp in ‘Praise the Lord with cheerful noise’ (1/12); the drama-laden chorus ‘Save us, o Lord’ (1/22); Gilchrist’s superb aria ‘O beauteous Queen’, with its graceful Handelian lines and rich scoring (1/25). The second CD brings us Act 3, generally more pompous in style (but not in a bad way!), opening with a magnificent, horn-rich introduction and chorus superbly delivered here by the Dunedins (2/1-2), music which Handel later lifted for one of his magnificent ‘Concerti a due cori’. The work concludes with an extended celebratory chorus, ‘The Lord our enemy has slain’ with fine solo and duet passages. Altogether Handel’s first oratorio is a rich, beautiful and varied work – as well as being a significant development in music history – and it receives a very fine performance here. Recorded sound, in Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Kirk, is excellent. John Butt’s booklet notes are a model of information and clarity, and full text is included – the latter in print so small that some way find it hard to read – all in English only. I would just finish by adding a word in favour of Handel’s later, 1732 version of ‘Esther’, which is very different, with much additional music and equally well worth the attention of enthusiasts of the composer’s work. At the time of writing there is one recording available of this latter, by the London Handel Orchestra and Chorus under Laurence Cummings. Review: Seductive and stylish ... - I bought this CD on the strength of John Butt's other 'period' Handel-at-Canons recording, Acis and Galatea, which I thoroughly enjoyed. This 'period' recording too is very satisfying. Professor Butt's scholarly awareness in recreating the original resources means he has chosen his musicians with care. The performance is supremely stylish, and colourful not least in the triumphant brass and elegant woodwind playing. Also triumphant and elegant in equal measure is the stylish singing by soloists and chorus; every word is crystal clear, every musical phrase well-drawn. The programme notes present in most readable fashion the fascinating back-story of Handel's time at Canons with the Earl of Carnarvon (later Duke of Chandos) and the work's early history. This is all very nicely done.

| ASIN | B0072H9BFE |

| Best Sellers Rank | 288,300 in CDs & Vinyl ( See Top 100 in CDs & Vinyl ) 11,193 in Opera & Vocal Music |

| Customer reviews | 4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars (13) |

| Is discontinued by manufacturer | No |

| Label | Outhere / Linn |

| Manufacturer | Outhere / Linn |

| Number of discs | 2 |

| Product Dimensions | 15.29 x 12.9 x 1.6 cm; 125.87 g |

S**Y

Beautiful performance of Handel’s first oratorio

This is Handel’s original, 1720 version of ‘Esther’ as composed for the Duke of Chandos – or rather, as John Butt explains in his scholarly but very readable booklet notes, the first ‘reconstructable’ version following an earlier draft originating from 1718. The composer later revised and greatly expanded the work, resulting in a final version of 1732 (as recorded by Laurence Cummings, listed and reviewed elsewhere). This ‘Esther’ then, Handel’s first oratorio and so the start of a long and distinguished tradition, is given a beautiful performance by the Dunedin Consort directed by John Butt. The graceful period-instrument textures and stylish playing of John Butt’s Dunedin Consort are immediately evident in the Overture, and of course continue throughout - including some lovely solo instrumental work. We get an equally fine team of vocal soloists, including tenor James Gilchrist outstanding in the role of Ahasuerus, soprano Susan Hamilton excellent in the title role, tenor Nicholas Mulvey’s Mordecai, and bass Matthew Brook’s forceful Haman. I don’t think much of countertenor Robin Blaze’s Priest of the Israelites, however - underpowered voice, expression nothing special either - but fortunately he doesn’t have a lot to do here. Special highlights for me include tenor Thomas Hobbs’ aria ‘Tune your harps’ (CD1/9) and its subsequent chorus (1/10); the lovely passages for flute and harp in ‘Praise the Lord with cheerful noise’ (1/12); the drama-laden chorus ‘Save us, o Lord’ (1/22); Gilchrist’s superb aria ‘O beauteous Queen’, with its graceful Handelian lines and rich scoring (1/25). The second CD brings us Act 3, generally more pompous in style (but not in a bad way!), opening with a magnificent, horn-rich introduction and chorus superbly delivered here by the Dunedins (2/1-2), music which Handel later lifted for one of his magnificent ‘Concerti a due cori’. The work concludes with an extended celebratory chorus, ‘The Lord our enemy has slain’ with fine solo and duet passages. Altogether Handel’s first oratorio is a rich, beautiful and varied work – as well as being a significant development in music history – and it receives a very fine performance here. Recorded sound, in Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Kirk, is excellent. John Butt’s booklet notes are a model of information and clarity, and full text is included – the latter in print so small that some way find it hard to read – all in English only. I would just finish by adding a word in favour of Handel’s later, 1732 version of ‘Esther’, which is very different, with much additional music and equally well worth the attention of enthusiasts of the composer’s work. At the time of writing there is one recording available of this latter, by the London Handel Orchestra and Chorus under Laurence Cummings.

M**G

Seductive and stylish ...

I bought this CD on the strength of John Butt's other 'period' Handel-at-Canons recording, Acis and Galatea, which I thoroughly enjoyed. This 'period' recording too is very satisfying. Professor Butt's scholarly awareness in recreating the original resources means he has chosen his musicians with care. The performance is supremely stylish, and colourful not least in the triumphant brass and elegant woodwind playing. Also triumphant and elegant in equal measure is the stylish singing by soloists and chorus; every word is crystal clear, every musical phrase well-drawn. The programme notes present in most readable fashion the fascinating back-story of Handel's time at Canons with the Earl of Carnarvon (later Duke of Chandos) and the work's early history. This is all very nicely done.

P**S

Five Stars

The full, later revision (1732) excellently performed.

G**O

This recording is a triumph of both musicology and musicianship, a "first" reconstruction of Handel's "first" sacred oratorio in English and the "first" evidence that Handel had already evolved a distinctly English style almost as different from his Italian manner as Purcell was from Carissimi. There are a couple of previous recordings of Esther, conducted by Harry Christophers and Nick McGegan, but they bear almost no similarity to the version recorded here, for the simple reason that Handel drastically rewrote Esther for a later occasion. The first Esther was a "house" concert at Cannons, the estate of the Duke of Chandos. The libretto may have included contributions by Alexander Pope. It's the story, told twice in the Bible, of the genocide of Jews in Persia decreed by the villain Haman in the name of his King Assuerus. The King, however, hears the appeal of his newly beloved wife Esther, who is herself Jewish, and revokes the decree. In the end, Haman's treacherous intentions are exposed and the villain is sent off to execution. The story is presented in a series of vignettes, almost as tableaux vivantes, that would not have required much explicit narration for an audience deeply familiar with every chapter of the Bible. The political climate in Puritan England in 1720 would NOT have tolerated a more public production of a performance that combined secular music with sacred texts. This first version of Esther was not entirely new. Much of the music was recycled from Handel's own setting of the Brockes Passion and from his English version of Acis and Galatea. Any listener who supposes that vocal music can be heard best by ignoring the text would do well to listen to Haman's final aria of lament, with its convincing affect of defiance and shame. The same musical notes were sung by Jesus in the Brockes Passion, with an utterly different emotional affect. As in previous Dunedin performances, the impact of the "whole" is greater than that of the parts, even when the parts are very fine. Tenor James Gilchrist is elegantly suave as Kind Assuerus, bass Matthew Brook is grimly fierce as Haman, and the rest of the cast, though not quite as polished as those two, are still musically thrilling to hear. It's the chorus, nevertheless, that constituted the 'originality' of this work as first conceived; no chorus in any of Handel's Italian works played such a prominent role. The Dunedin Consort chorus consists of the five principals each doubled by another singer, comprising a vocal force grand enough to be impressive yet small and coherent enough to sound like human voices issuing from the speakers of your sound system. The orchestra, with full string sections plus two horns, trumpet, flute, two bassoons, and harp, supports the singers with a rich structure of sonorities. Dunedin has already given us some extraordinary interpretations ... Handel: Messiah (Dublin Version, 1742) Byrd & Tallis: ...In Chains Of Gold... J.S. Bach Mass in B Minor George Frideric Handel: Acis and Galatea ... and others, every one of which is alive with musical insight and excitement.

T**R

I wanted to like this, but compared to the recording by Harry Christophers and The Sixteen it presents few differences in text and music and showcases an uneven cast. Comparison with Christopher's Lynda Russell, Nancy Argenta, Michael Chance, Mark Padmore, Tom Randle and Michael George, shows all of Butt's cast to be weaker - in some cases remarkably so. Matthew Brooks, Nicholas Mulroy and James Gilchrist are very good and just a shade below George, Padmore and Randle, but Susan Hamilton and Robin Blaze suffer much when placed next to Russell and Chance. Blaze sounds unsteady, occasionally unsupported and has to resort to an awkward shift into chest (real?) voice below the staff. Hamilton's voice is light, girlish, has a beat in the middle register and is without much character. Her jubilant aria sounds more maniacal than happy and features a badly judged descent into an ugly chest voice. The difference from Butt to Christophers is that Christophers uses a structure of six scenes while Butt uses a division into three acts. Both were used by Handel at various times. The sequence of numbers remains the same and the orchestration sounds similar (Christophers employs a theorbo). One chorus is different. Butt's orchestra and chorus are similar in numbers to that employed by the Duke of Chandos at Cannons about 1718/20. Christophers groups are about 50% larger. The orchestras for both are excellent and the sound of both is good, with Linn having more "presence". The perspective in the Christophers is from the middle of the hall; with Butt you are sitting front row center (or maybe right on the stage.) Both performances take about 100 minutes, with Christophers inserting a lovely Handel oboe concerto between two scenes for an additional six minutes.

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

3 days ago